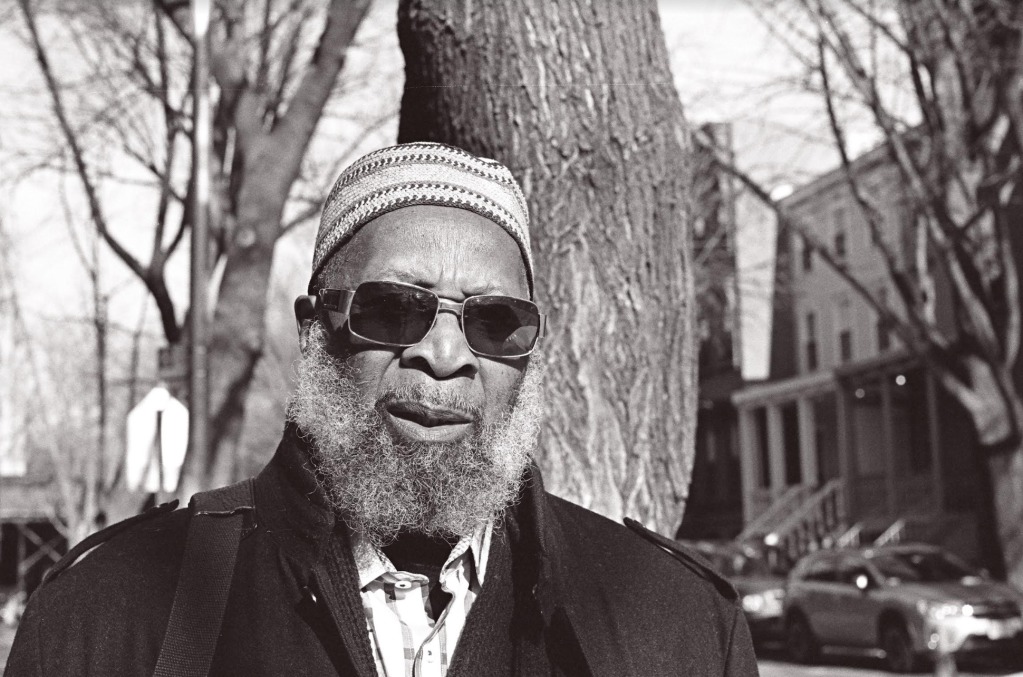

On January 12, 2024, the dedicated freedom fighter, Sekou Odinga, died at the age of 79. His passing belongs to a series of recent deaths of giants of the Black Nationalist world, including Mutulu Shakur, Viola Plummer, and Iyaluua Ferguson, who are also undeniably important figures for all serious students of the oppositional political history of NYC: Harlem of the time of Malcolm X, Ocean Hill-Brownsville 1968, the case of the Panther 21, and much more. Following his release in 2014, after surviving 33 years in prison, Sekou spent the last decade of his life campaigning for the release of other political prisoners, founding the Northeast Political Prisoner Coalition (NEPPC). In March 2021, we hosted an event with Sekou as the featured speaker to spread awareness among students of the dire conditions faced by the remaining political prisoners of the Black Liberation movement of the sixties.

Some of Sekou’s last reflections on his life and political contributions can be found in his essays “Legacy: Where We Were, Where We Are, Where We Are Going” in Black Power Afterlives (2020) and “Still Believing in Land and Independence” in Look for Me in the Whirlwind (2017) (a reissue of the 1971 collective autobiography of the Panther 21), as well as on the Black Power Media podcasts “Black Liberation Army: Soldiers’ Stories” (2021) and Renegade Culture (July 4, 2020 episode).

I.

On April 3, 1969, heavily-armed police carried out a wave of early-morning raids throughout NYC, aiming to arrest members of the Black Panther Party (BPP). A sensationalist New York Times cover story joined the action: “Black Extremists Accused of Planning Explosions at Macy’s and Elsewhere.”

Founded in Oakland in October 1966, the BPP of Huey Newton and Bobby Seale had been in existence in NYC for only about a year when the Panther 21 were indicted in April 1969.

In early 1968, while Huey sat behind bars in CA awaiting trial for a murder charge stemming from an October 1967 police encounter, the BPP was rapidly expanding to Los Angeles, Seattle, New York, and more than two dozen other cities. In NYC, Sekou Odinga and his friend Lumumba Shakur helped to establish the chapter as founding members, respectively becoming Bronx and Harlem section leaders. Earlier, both briefly had been members of Malcolm X’s OAAU. “New York was alive with political debate, if you went up to Harlem, parts of Brooklyn…. I met Baba Herman Ferguson in Queens around that time. That actually was the first political event on the streets I ever went to, a rally to try to get Baba Ferguson back into a teaching position where they had pushed him out because of his radical politics.” (Sekou on the Renegade Culture podcast). In addition to Ferguson, the Black Nationalist school administrator then at the center of the clash over school decentralization, Lumumba’s father Haji Abba Salahdeen Shakur was likewise a supporter of Malcolm X and became a mentor to Sekou, Mutulu, Afeni, and scores of other youth. Lumumba’s own brother Zayd, also a Panther, would later be killed by police in the 1973 NJ Turnpike encounter that led to the arrests of Assata and Sundiata Acoli.

At the same time (early 1968), while NYC’s decades-long nationalist tradition, dating back to Marcus Garvey’s UNIA, the originator of the Red, Black, and Green flag, was finding its way into the new organizational form of the BPP, Detroit’s Malcolm X Society, led by the Obadele brothers, was convening the founding of the Republic of New Afrika (RNA). Queen Mother Moore was the first of 100 signatories of the RNA Declaration of Independence. Robert Williams, in exile in Maoist China, was elected RNA president. Sekou became a “conscious citizen,“ in the parlance of the RNA, in 1968.

Parallel to this, influenced by Eldridge Cleaver’s “Black Paper” (see the May 4, 1968 issue of The Black Panther), Huey amended Point 10 of the BPP’s 1966 platform and program in May 1968, adding the following: “We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace, and as our major political objective, a United Nations-supervised plebiscite to be held throughout the black colony in which only black colonial subjects will be allowed to participate, for the purpose of determining the will of black people as to their national destiny.“ However, later, the December 6, 1969 issue of The Black Panther would carry an open letter by Huey to the RNA, calling for closer work on political prisoners, but outlining differences between the perspectives of the BPP and the RNA: “[I]t’s simply a matter of timing. We feel that certain conditions will have to exist before we’re even given the right to make that choice. … [W]e’re not really handling this question at this time because we feel that … it is somewhat premature …. I think that it would be perfectly justified if the Blacks decided that they wanted to secede the union, but I think the question should be left up to the popular masses.” (full)

II.

Targeted among the Panther 21, Sekou, already living underground at the time, eluded arrest in the April 1969 police raids by climbing out of a window, earning his “Spiderman” nickname. By the next year, he was in Algeria, then approaching only the eighth year of its independence from France.

The list of the other 21 indictees included many now recognizable names, such as Sundiata Acoli, Kuwasi Balagoon, Jamal Joseph, Richard Moore (Dhoruba bin Wahad), Curtis Powell (a University of Stockholm PhD who later worked on a vaccine against sleeping sickness), Afeni Shakur, and Michael “Cetewayo” Tabor. The Panther 21 trial, at the time the longest in NYC history, ended in full acquittals on May 13, 1971, a final demonstration of the baseless and state-fabricated nature of the indictment.

However, the BPP was by then an organization in crisis, a consequence of both COINTELPRO disruption and internal contradictions: in January 1971, the Panther 21 had published an open letter to the Weather Underground, greeting it as “one of” “if not the true vanguard” for having “related to action,“ obliquely criticizing their own party (“have a newspaper, hold rallies, conventions, congresses, etc.—then rhetoricians rhetoric, functionaries function, printing presses print …,“ etc.), and supporting an orientation of “action” by a “handful,” by “small groups” with quotations from Sartre’s Preface to The Wretched of the Earth, Che, two leaders of the struggle in Brazil against the military regime of 1964 (Marighella and Ladislau Dowbor), and George Jackson (who coincidentally would end up siding with the Newton-Hilliard camp in the ensuing BPP split, outlining his views in a letter later included in Blood in My Eye). After Dhoruba bin Wahad and Tabor soon jumped bail in the ongoing Panther 21 trial, the February 13, 1971 issue of The Black Panther published an article denouncing them as “enemies of the people” and announcing the expulsion of the 21 from the BPP “for their attacks on the Party in their letter to the Weatherman” (a “counter-revolutionary statement”).

The subsequent events are mostly known: the February 26 confrontation on live TV between Newton in studio in SF and Cleaver calling from Algiers, the expulsion by Newton of the Algiers-based Panthers, and the development of the Black Liberation Army (BLA) from certain preexisting foundations on the one hand and the closure of the BPP’s local chapters to focus Oakland municipal politics on the other. Reflecting their divergent paths, in the same year of the NJ Turnpike encounter involving the BLA (1973), BPP Chairman Bobby Seale would come in a distant second place in Oakland’s mayoral race.

The 1971 open letter of the Panther 21 had publicized a relation, based on the emergence of a common orientation, that would develop over the course of the WUO’s 1974 publication of its book Prairie Fire and its split in the aftermath of the 1976 Hard Times Conference in Chicago. Around the turn of the decade, some of the last free remnants of the BLA, which was largely neutralized as a fighting force already by 1974-5, would join with an offshoot of the WUO’s tendency in two actions: Assata’s escape from prison (1979) and the disastrous attempted Brinks robbery (1981). The arrestees after Brinks and in the following years demonstrated the proximity of the “strategic alliance” that had formed: Kathy Boudin, Judith Clark, David Gilbert, Sekou, Mtayari Shabaka Sundiata (killed by police), Kuwasi Balagoon, Silvia Baraldini, Jamal Joseph, Marilyn Buck, Linda Evans, and Mutulu Shakur. For one recent account of this period, see the 2022 podcast Mother Country Radicals produced by Zayd Dohrn.

III.

Sekou’s work developing the BPP’s section in independent Algeria, from 1970 until his arrival back in the US (“His leaving the safety there to come back to the U.S. spoke volumes about his commitment to the freedom struggle.” —David Gilbert in his 2012 memoir), brings up, of course, a national cause that is on the minds of many students: Palestine. In “Still Believing in Land and Independence” (2017), as well as on the podcasts linked at the start, we learn of the closeness of Sekou’s direct relation to the Palestinian struggle, embodied during this period by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) of Yasser Arafat. However, to discuss the PLO in 1970 today is to return to an entirely different world. It is to consider, by contrast, the nature of the turning point represented by the disorienting world events of 1979-1981: the Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia four years after the liberation of Saigon, the Iranian Revolution, the Carter-Reagan transition under the impact of the embassy episode in Iran, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Iran-Iraq war, China’s official condemnation of its Cultural Revolution…. That is to say, a world that looks more like it is today.

In the US, former RNA leader Chokwe Lumumba briefly became mayor of Jackson, Mississippi in 2013, before unexpectedly dying in office. His son Antar Lumumba has been mayor of the city since 2017. More recently, Kathy Boudin and David Gilbert’s son Chesa Boudin became SF District Attorney for a little more than two years on a progressive platform, through the height of the pandemic, before succumbing to a recall election in 2022. Meanwhile, each new generation becomes increasingly distant from the real history and debates of the past, settling instead for names, symbols….